Any health plan ultimate goal is to improve health and to reduce health inequities, with minimum resources, based on a value for health approach. A local health plan should follow strategic orientations from European, national and regional levels in order to achieve the sustainable development goals established by the World Health Organization. This idea of top-bottom guidelines is fundamental, although the usual short time frame may affect the evaluation of its implementation in terms of outcomes and impact.

Building Local health plans is responsibility of the public health team and health planning is its cornerstone. Also, it represents a social commitment, since it involves collaboration between stakeholders and individuals of a community in all of its phases. These interested parties are numerous actors that play a role in the community, taking direct or indirectly action in the health of the population. Their interventions should contribute to Health in All Politics (no longer policies) concept, and represent a stronger and empowered view of the results that all actions can have on community’s health and well-being. The plan should have a strategic format to provide all stakeholders with the right tools to take it into action; always in a whole-of-government and whole-of-society point of view. They should be diverse in their activities, in order to reach all citizens in different life settings. However, family, school, workplace, healthcare institutions and social environment are priority contexts and require the most adequate interventions.

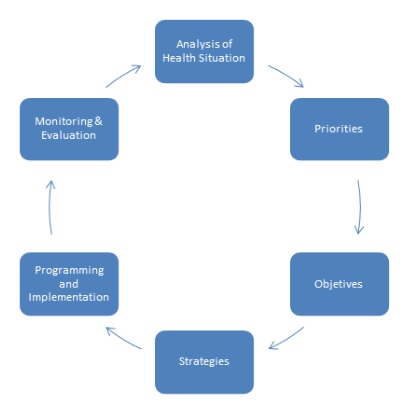

Local health plans are based on the stages of the health planning cycle (figure 1) and start with an analysis of the local health situation assessment, withdrawn from the local health observatory. This information allows the drawing of the first list of health problems and their determinants, which, subsequently, are prioritized. The next step involves the setting of objectives and selection of strategies in collaboration with all stakeholders, taking into account the main health problems identified. During and after the implementation of the plan, it should be monitored and evaluated, as these are important components to ensure its fulfillment, using core indicators.

The health planning cycle should never be interpreted in a two dimensional (2D) perspective. Its structure allows transforming all outputs from evaluation phase to inputs used in the next step. Therefore, from a 3D analysis, the health planning cycle is a spiral which ends in an ideal health condition (utopian perception). It may be considered an iteration cycle, a process used to make anything better over time.

Therefore, a local health plan is a fundamental tool to implement the best practices available and improve population health. Its use must be encouraged and widespread. The importance of stakeholders in all course of action is their multisectoral response and their ability to build bridges between them, centered on population health and well-being. Thus, the interested parties should cover all society sectors based on Health in All Politics approach, leading decision makers to innovate and going beyond an ordinary policy plan.

_________________________

References

- World Health Organization. National health policies, strategies, and plans. http://www.who.int/nationalpolicies/resources/resources_tools/en/ [Online]

- Manual Orientador dos Planos Locais de Saúde. Direção-Geral da Saúde – Plano Nacional de Saúde. Lisboa. Janeiro, 2017

- Metodologia do Planeamento da Saúde. Imperatori and Giraldes. Lisboa. 1982

- La Planification Sanitaria. Pineault and Daveluy. Barcelona. 1994

_________________________

João Paulo Magalhães

Public Health Resident

Community Health Center Group of Porto Oriental, Public Health Unit