This July the UK celebrated 70 years of the National Health Service which famously entitled healthcare to all “from cradle to grave”. Unfortunately progress on universal healthcare in the post-colonial Irish state has been much slower. In May 2017, a cross-party parliamentary committee produced a 10-year plan for the future of healthcare. Their report was called the “Sláintecare Report” (Sláinte translated from Irish means health) (1). It was ambitious with many recommendations including:

- The phasing out of private care in public hospitals

- Eliminate charges for access to public hospital care

- Reduce drug prescription charges

- Universal access to GP care without charge

- Expand public hospital capacity

- Reduce waiting lists for first outpatient department appointments and hospital treatment

However, progress on implementation has been slow and the signs are that the required funding will not be made available in the next budget. This is not the only barrier to implementation, doctors’ unions including the Irish Medical Organisation have come out against the plan to remove private medical practice from public hospitals (2).

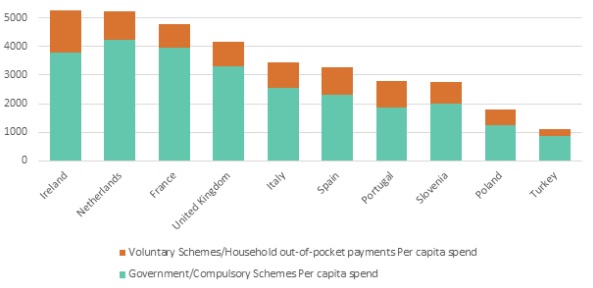

This points to an important aspect within an Irish healthcare system which is the role of private healthcare. Figure 1 shows that amongst Euronet countries for which data is available from the OECD, Ireland has the highest per capita spend on healthcare and the highest spend on voluntary private health care and out of pocket payments (3).

The Whitehall Studies, led by Sir Michael Marmot, was a prospective cohort study of civil servants in the UK between 1967 and 1988 which examined the relationship between mortality and employment status. They demonstrated that even when controlled for lifestyle factors such as, smoking status, blood pressure, obesity and cholesterol, mortality rates followed a gradient from those of lowest status to those of highest status. For instance, those men in the lowest grade had a mortality rate three times that of the highest grade (4).

This result showing a social gradient in health outcomes has been replicated many times and the idea of “Proportionate Universalism” was coined by Sir Michael Marmot and proposed as a means of addressing this gradient of health inequalities in the “Marmot Review” (5). It describes public health interventions which are aimed at the entire population, universal, but which are proportionally weighted in favour of those in most need.

Proportionate Universalism has shown success in reducing health inequalities in the UK by addressing inequalities in healthcare provision and in the social determinants of health (6). However, it is not clear this means of addressing health inequalities would be sufficient to make a meaningful difference in an Irish context.

The continuum of health need in Ireland is not linear, with a major influence on this based on the marketization of healthcare within the system. Those who can afford Private Health Insurance have better access to hospital consultants and diagnostics, even within the public system (7). On top of this there are further financial barriers in out-of-pocket payments for primary care and prescriptions. Like Julian Tudor Hart described in his paper on the “Inverse Care Law”, those with most need have the least access to services (8).

The two tiered nature of the Irish healthcare system was encapsulated in the name of a book written 10 years ago on the subject called “Irish Apartheid”. If a Proportionate Universalism public health strategy is to be effective in Ireland we must follow the example of our European neighbours and move towards universal healthcare, oppose doctors who wish to protect their private practice and give our support to the spirit of Sláintecare.

_________________________

References

- Shorthall R. Houses of the Oireachtas Committee on the Future of Healthcare Slaintecare Report. Houses of the Oireachtas: Oireachtas; 2017.

- Irish Medical Organisation. Irish Medical Organisation Submission to the Independent Review Group on Private Practice in Public Hospitals. Dublin: Irish Medical Organisation; 2018.

- Health expenditure and financing: Health expenditure indicators [Internet]. OECD Health Statistics (database). 2018 [cited 29 July 2018]. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/data/data-00349-en.

- Marmot MG, Stansfeld S, Patel C, North F, Head J, White I, et al. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. The Lancet. 1991;337(8754):1387-93.

- Marmot M, Allen J, Goldblatt P, Boyce T, McNeish D, Grady M. Fair society, healthy lives. The Marmot Review. 2010;14.

- Egan M, Kearns A, Katikireddi SV, Curl A, Lawson K, Tannahill C. Proportionate universalism in practice? A quasi-experimental study (GoWell) of a UK neighbourhood renewal programme’s impact on health inequalities. Social Science & Medicine. 2016;152:41-9.

- Burke SA, Normand C, Barry S, Thomas S. From universal health insurance to universal healthcare? The shifting health policy landscape in Ireland since the economic crisis. Health policy. 2016;120(3):235-40.

- Hart JT. The inverse care law. The Lancet. 1971;297(7696):405-12.

_________________________

Christopher Carroll

Specialist Registrar in Public Health Medicine, Ireland