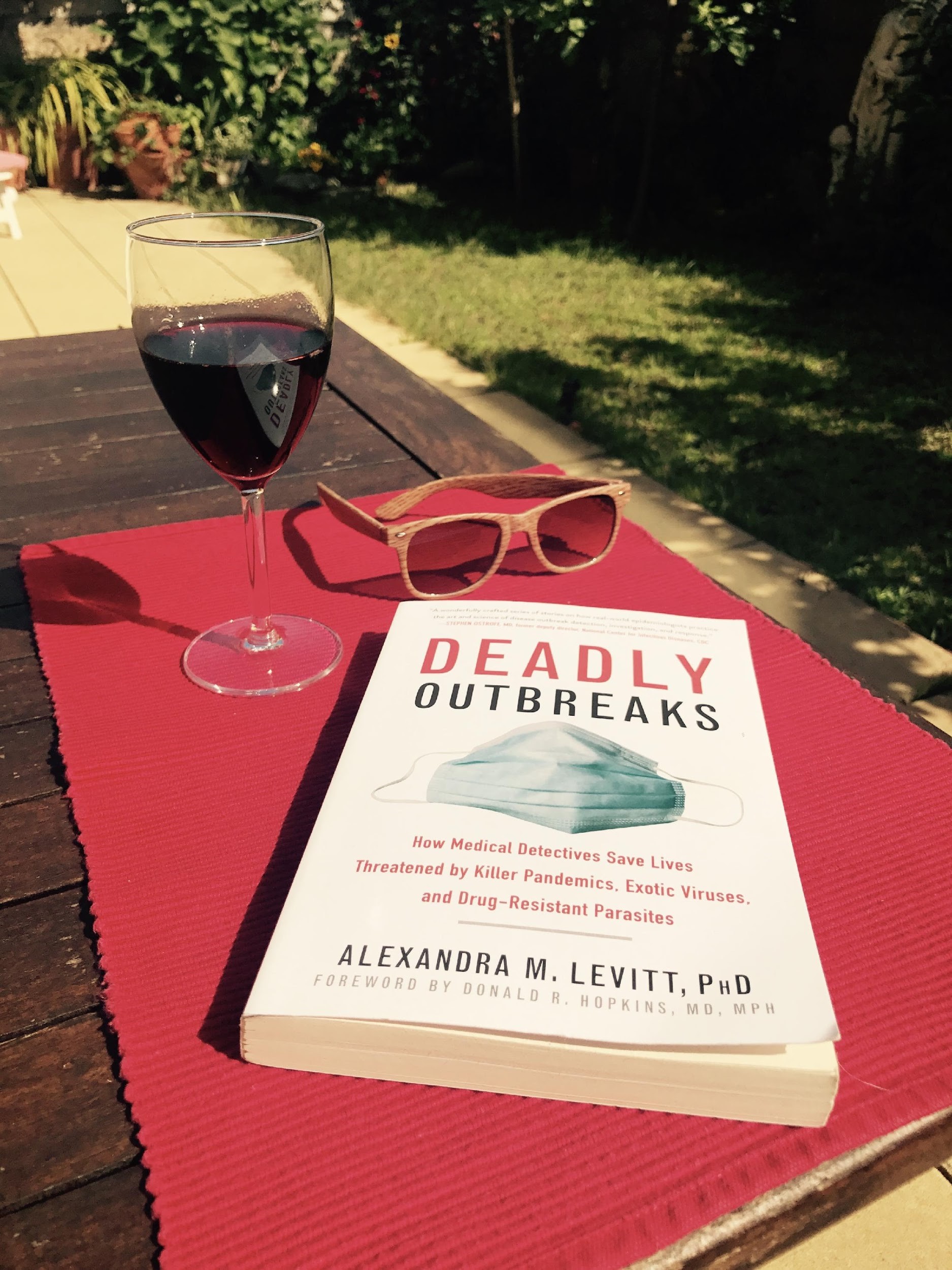

Summer time, hot weather, (almost) everyone on vacations… Well, not me! But during the weekends I choose to hang out at the terraces of nice cafes, enjoying the good weather with some friends. I could tell you I usually drink water and natural juices in these occasions but I would be lying: a glass of red wine or some nice sangria are my options on these relaxed afternoons. It is the perfect timing to read a nice book, too. The last one I read was “Deadly Outbreaks” by Alexandra Levitt(1) and was result of a purchase on the internet, while searching for books on public health issues.

Before going to medical school, I was already working in infection control area at a 400 bed hospital, where epidemiological surveillance is an important component of our functions and, I must admit, one of my favorites. During these 13 years of work at this hospital, I already had to deal with few outbreaks but it was the one in the summer of 2006 I remember the most, when I was still a “freshman” in the Infection Control Committee. At the time, the microbiology laboratory gave us an alert: multidrug-resistant (MDR) Acinetobacter baumannii was isolated in sputum of a trauma patient transferred from a central hospital some days before. After a first assessment we found out he was located in the Surgical Intermediate Care Unit, a small pos-op infirmary “packed” with 6 patients, where the distance between beds was roughly 1,5 meters and in which “our” patient was frequently coughing and in need of nursing care. This microorganism was not part of our local ecology, so this was considered an infection control “code blue”! The patient and the unit were immediately put in contact isolation, while the lab confirmed other two positive patients for MDR A. baumannii. An outbreak was officially declared and, with the support of the hospital management, rigorous infection control measures were taken: all contacts with this patient were identified and put in contact isolation, an epidemiological line list was done and an active surveillance protocol was implemented. The unit was closed to new admissions, environment hygiene measures were reinforced, patients were stratified by risk level and a cohort of healthcare workers (HCW) was put in place (specific teams of HCW took care of “confirmed”, “suspected” and “negative” patients). Meanwhile, the hospital that transferred the index patient warned us that they were experiencing problems with this microorganism but this information came to us too late… After eight months, 15 cases (8 of which died), 61 patients put in isolation and surveillance, and a lot of effort (and costs) for the hospital, HCW’s and patients, the outbreak was finally controlled. As a consequence of it, a surveillance protocol for MDR A. baumannii was implemented (applied for all patients transferred from other hospitals). In my opinion, one of the “lessons to be learned” from this outbreak is the importance of communication between and within healthcare units to be able to minimize infection control risks, related to patients mobility. Twelve years have passed and, today, this and other hospitals have a risk evaluation procedure that is applied to all admitted patients.

But back to the book: if you liked this outbreak description, you will LOVE “Deadly Outbreaks”1 and you won’t be able to sleep until you end it! The author, Prof. Alexandra Levitt, is an expert on emerging diseases and other public health threats and worked for the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). She dedicates this book to all field epidemiologists that “save lives threatened by killer pandemics, exotic viruses and drug-resistant parasites”. The book describes, in an exciting and pedagogical way, seven public health mysteries occurred in the United States of America between 1976 and 2006, through the learn-by-doing approach of the “medical detectives” of CDC´s Epidemic Intelligence Service. In the “author’s note”, three advices are given, namely: “be prepared for the unexpected” (when it comes to infectious microorganisms); “we are all in it together” (with the phenomena of globalization, wherever we live, we are all at risk) and the importance of participating in a strong public health system, in the pursuit of prevention of disease spread among the community.

In one outbreak described in the book, investigating the mysterious death of several infants at a Children´s Hospital, several epidemiological tools were used, including the “epi-curve” and the “relative risk of death” associated with each nurses’ shifts, estimating the risk of a baby dying when a specific person was on duty. The study concluded that the hospital should strengthen central control of medicines and implement a monitoring system of deaths, by time and place, within the hospital. (2)

Did you know that, as a consequence of an outbreak in a Philadelphia hotel affecting middle-aged Legionnaires, CDC fielded one of the biggest investigative team ever but couldn´t find its etiological agent for several months? In fact, it was a young microbiologist of CDC that discovered it when, later on, decided to review and explore the finding of some rods that he, first, assumed were contaminants of his cultures (“be prepared for the unexpected”, remember?). Did you know that, after its discovery in 1976, Legionella pneumophila was retrospectively implicated in cases as far as 1943?

More recently, did you know that an epidemiologic outbreak investigation, affecting abattoir workers exposed to porcine brain, led to the discovery of an immune-mediated polyradiculoneuropathy? (3)

Throughout the book, these and many other epidemiological and infectious diseases facts are given, engaging the reader to explore the scientific method, by testing various hypotheses through the use of the technologies available at the time of the outbreak. At the end of each chapter, the author reviews the main facts to illustrate the lessons learned. Did I catch your attention? Hope so! Despite the book portraying the modus operandi (and available associated resources) of the North-American reality, it’s full of interesting facts that, in my opinion, will enrich our knowledge in public health area. A “must-read”!

_________________________

References:

- Levitt, Alexandra M (2015) Deadly Outbreaks. 2nd edition. New York: Skyhorse Publishing.

- Buehler JW, Smith LF, Wallace EM, Heath CW Jr, Kusiak R, Herndon JL (1985) Unexplained deaths in a children’s hospital – An epidemiologic assessment. N Engl J Med; 313(4):211-6.

- Holzbauer SM, DeVries AS, Sejvar JJ, et al. (2010) Epidemiologic investigation of immune-mediated polyradiculoneuropathy among abattoir workers exposed to porcine brain. PLoS One. 5(3):e9782.

_________________________

David Peres

Public Health Resident

Public Health Unit – Community Health Center Group of Povoa de Varzim / Vila do Conde (Portugal)